Baltimore Orioles radio play-by-play announcer Joe Angel still chuckles when he recalls the time last year when former Orioles pitcher Ben McDonald, during one of his stints in the booth as an analyst, made one of the more mundane moments of the broadcast unintentionally hilarious.

“We have this disclaimer we have to read once a game about how you can’t copy them or use them for your own purposes, and there’s a word in that disclaimer: ‘disseminated,'” Angel said. “Well, Ben went two or three days and he could not say ‘disseminated.’ He kept saying something like ‘dis-se-seminated.’ He did it in that Southern drawl, and we were both cracking up in the booth. You could almost hear people laughing along on the radio, saying, ‘Ah, that’s Ben. What a great guy.’ Even when he can’t do something, people like him.”

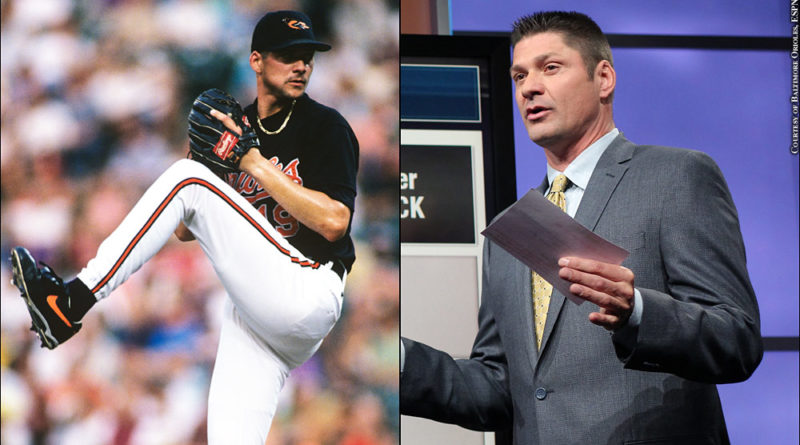

McDonald’s folksy demeanor, combined with his baseball knowledge and infectious love for the sport, has made him a favorite of listeners and viewers of Orioles radio and television broadcasts since he began working with the club as an analyst for select games in 2010. This season, fans will get to hear more of McDonald than ever, as he will take part in more than 30 games on the Orioles Radio Network beginning in late July.

It’s fitting that Baltimore has a role in the second act of McDonald’s professional life. One of the most heralded prospects of all-time, McDonald was selected by the Orioles as the No. 1 overall pick in the 1989 Major League Baseball Draft. McDonald played seven seasons in Baltimore, and though he experienced his share of highs and lows during his time in orange and black, McDonald was thrilled when the Orioles asked him to join their broadcast team.

“I tell people all the time that Baltimore is where I grew up and became a young man,” said McDonald, a Louisiana native who resides in Denham Springs, near Baton Rouge. “I was a 21-year-old kid when I came to Baltimore, and I didn’t know anything about anything. The fans really took me in, and Baltimore has always been a home away from home for me. When I got the chance to come back, gosh, I felt like I was home again.”

McDonald, 50, began his broadcasting career as an analyst for his alma mater, Louisiana State, on a regional television network in 2003, several years after his playing career was cut short due to shoulder injuries. The College Baseball Hall of Famer also works as a college baseball color commentator for ESPN and the SEC Network.

Angel, who has the distinction of being the play-by-play announcer for McDonald’s major league debut in 1989 as well as his first major league radio broadcast as an analyst more than 20 years later, said McDonald is a natural in the booth.

“Ben’s friendly, he’s a good storyteller and he has credibility,” Angel said. “People believe what he says and they love the way he says it. That’s a pretty good combination to have.”

That McDonald is an entertaining commentator should come as no surprise to anyone who remembers the character he was as a player. The jocular McDonald once put an alligator in the bathtub of a teammate while in the Florida Instructional League, and during a rain delay at Oriole Park in 1993, he donned a floppy hat, got his rod and reel and went “fishing” in the flooded dugout.

McDonald’s transition from player to commentator was not seamless, however. In fact, when he had no choice but to retire in 1998 at the age of 30, the gregarious country boy sank into a depression that lingered for months.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

To say McDonald was the very definition of a phenom would be an understatement. With his extraordinary talent — he received Major League Scouting Bureau’s highest score ever — gangly body and proclivity for wrestling alligators in the Louisiana bayous, the 6-foot-7 right-hander who also played basketball in college was a real-life Sidd Finch, the fictional baseball sensation rolled out in an April Fool’s issue of Sports Illustrated in 1985.

It was a foregone conclusion that the Orioles would select the hard-throwing junior from LSU with the first pick in the 1989 draft. That the Orioles would actually be able to sign the “golden boy” — he led the U.S. Olympic baseball team to gold in 1988 and won the 1989 Golden Spikes Award as the nation’s best amateur baseball player — was much less certain.

After more than two months of intense negotiations between Orioles president Larry Lucchino and agent Scott Boras, the two sides finally reached an agreement on a three-year, $950,000 contract, which at the time was the second-highest ever given to an amateur baseball player (the Kansas City Royals had given Bo Jackson a $1.1 million deal in 1986 to lure him from the NFL), and a then-record $350,000 signing bonus.

Less than three weeks after signing, McDonald made his major league debut Sept. 6, 1989 at Memorial Stadium, coming on in relief against the Cleveland Indians with two runners on base and one out in the third inning with the Orioles trailing, 4-0. He threw one pitch and got an inning-ending double play. That was impressive for sure, but not as impressive as McDonald’s first major league start, which he made against the Chicago White Sox at Memorial Stadium July 21, 1990. He pitched a complete-game shutout, throwing just 85 pitches during a 2-0 victory. McDonald also won his next four starts, putting his record at 5-0 with a 1.55 ERA.

At that point, giddy Orioles fans likely envisioned multiple Cy Young Awards for McDonald and his likeness emblazoned on a bronze plaque in Cooperstown, N.Y., but the reality would be much different. After winning his first six decisions, McDonald went 52-53 with the Orioles before leaving as a free agent after the 1995 season to sign with the Milwaukee Brewers. For his career, McDonald was 78-70 with a 3.91 ERA in nine seasons.

Reflecting on his years with the Orioles, McDonald said the ridiculously high expectations weighed on him.

“I remember my second year, Frank Robinson was the manager, and he said in public that if we were going to have a chance of winning that year I was going to have to win 20 games,” McDonald said. “I’m thinking, ‘I don’t even know how to pitch yet and you’re telling me that I have to win 20 games.’ All of a sudden, you start trying to live up to that. It spiraled out of control for a while for me. There was so much hype that the fans expected it, too. Of course, it wasn’t their fault; I was supposed to do all these things at an early age. I just think the expectations were unrealistic at that point.”

McDonald’s stuff was undeniable; the problem, he said, was that he didn’t understand how to use it.

“I was in a man’s game all of a sudden,” he said. “My college coach had called every pitch I ever threw at LSU. … Whatever he called, I just threw and never really understood why I was doing it. Now I’m in the big leagues and, heck, I have to call my own game against the best players in the world.”

McDonald’s battery mate in 1991 was a young Chris Hoiles, who also was learning on the job, so shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. called McDonald’s pitches that season. When veteran pitcher Rick Sutcliffe signed with the Orioles in 1992, he served as a mentor to McDonald and often called his pitches from the dugout.

“I was also 6-[foot]-7, and I was a first-round pick by the Dodgers and a lot of expectations were placed on me,” said Sutcliffe, now a baseball analyst for ESPN. “I was just able to share a lot of my experiences with him and just let him take it from there.”

Said McDonald: “When Rick Sutcliffe came over, I had a veteran guy that I could lean on a little bit and bounce stuff off of. That helped my maturing process a lot. … I felt like I was on my way and had some things figured out, and the numbers really proved that.”

McDonald’s ERA went from 4.84 in 1991, to 4.24 in 1992, to 3.39 in 1993. In the strike-shortened 1994 season, he went 14-7, finishing fourth in the American League in victories.

“Then injuries started happening,” McDonald said, “and it was downhill from there.”

‘JUST NOT MEANT TO BE’

Tendinitis in McDonald’s shoulder limited him to 13 starts with the Orioles in 1995, as he went 3-6 with a 4.16 ERA. He rebounded to go 12-10 with a 3.90 ERA with the Brewers in 1996, but shoulder problems returned the following year, and he had to undergo season-ending surgery to repair his torn rotator cuff. McDonald was traded to the Indians after the 1997 season, but he would not throw a single pitch for them.

When McDonald walked off the mound at Milwaukee County Stadium after retiring the Indians in order in the sixth inning July 16, 1997, he had no idea it would be his final appearance in the majors. He was four months away from his 30th birthday.

After McDonald underwent two subsequent shoulder surgeries, renowned orthopedic surgeon Dr. James Andrews delivered the news McDonald had been dreading.

“He said, ‘Listen, go find you a fishing pole and go do something else,'” said McDonald, who underwent three rotator cuff surgeries. “He said, ‘You’ve worked as hard as anybody I’ve seen go through rehab, and we all did the best we could do. It’s just not meant to be. You’ve got to move on.'”

“It was like someone hit me in the head with a hammer,” McDonald said of his reaction when Andrews told him his playing career was over. “All I had known since the time I was 5 years old was sports. I’m supposed to be in the prime of my career. I’ve just now got it figured out and now you tell me I can’t do what I love anymore. It was an adjustment to say the least.

“There was depression. I just moped around the house. I really wasn’t much fun to be around for my wife and [young daughter]. It almost cost me my marriage; almost cost me a lot of things. I kind of turned my back on everything.”

McDonald said he was in a funk for about six months before he finally was able to come to grips with his situation.

“I’ve always enjoyed being outdoors and hunting, and that’s what really helped pull me through it,” he said. “I was able to go out in the woods by myself and sit up in a tree and just think about things and go back through the whole process. The more I thought about it, I realized, ‘Hey, some things just aren’t meant to be.’ I saw the best doctors. We rehabbed the heck out of it. We did everything we were supposed to do and it just didn’t work. At the end of the day, I can live with that now.”

McDonald decided to make the best of his newfound time at home by getting more involved with his family. His and his wife Nicole’s daughter, Jorie, was a preschooler when he retired, and their son, Jase, was born a few years later. When his kids began playing sports, McDonald coached their teams, including Jorie’s traveling softball team, which went on to win two national summer league titles. (McDonald will coach 17-year-old Jase’s summer league baseball team before he heads to Baltimore.)

McDonald’s professional future remained uncertain.

“I remember saying to myself that [having to retire] is not going to define me as a human being and what my life is going to be about,” McDonald said. “I got the rest of my life in front of me. What am I going to do from here on out? I knew I was going to stay busy hunting and fishing, but I also wanted something else, too.”

TALKING BASEBALL

That “something else” presented itself several years after his playing career ended when he ran into his old college baseball coach at LSU, Skip Bertman, who told McDonald that Cox Sports Television, the regional network that broadcasted LSU’s baseball games, was looking for a color analyst.

“I told him I’d never done it before, but he said, ‘You’d be great,'” McDonald said. “I kind of jumped in feet first not having a clue what all it took and the prep work. I started off without a score pad or anything, just up there talking about baseball.”

McDonald made enough of a positive impression that ESPN came calling that same year to have him work a Super Regional in Baton Rouge. That led to him doing about 15 LSU baseball games a season for the next several years in addition to getting more work with ESPN and eventually the SEC Network. He announced his first College World Series in 2017.

Including his Orioles gig, McDonald will do more than 100 games this year.

“About 10 years ago it went from a hobby to a job,” McDonald said. “I’m still an old country boy at heart, and I don’t necessarily enjoy all the travel, but I love it once they say ‘play ball’ and I get to talk about baseball. It’s fun for me.”

In 2010, the Orioles brought in McDonald and fellow former Orioles stars Eddie Murray, Brady Anderson and Mike Boddicker to serve as color analysts on television and radio broadcasts on a rotating basis, each of them doing about a dozen games. McDonald instantly connected with the audience and has returned to Baltimore every year since to take part in select broadcasts.

“Ben knows what he’s talking about and he also has that down-home folksiness that people really enjoy hearing,” said Fred Manfra, the longtime Orioles radio play-by-play announcer who retired last season. “He has those expressions from the South that come up during the course of a broadcast. It’s like a young guy watching the game of baseball with exuberance and using the same phrases he used growing up.”

One of the first people McDonald goes to when he comes to Baltimore to get up to speed on the club is Orioles Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Palmer. During McDonald’s playing days, Palmer was someone he would talk to about pitching.

“Whether you’re Ben McDonald or Jim Palmer or anybody that is a player or broadcaster, there’s not a day that you don’t go to the ballpark and learn something new or see something different,” said Palmer, who is in his 26th season as an Orioles television analyst. “From what I’ve seen of Ben, he’s certainly embraced that, and he’s got the aptitude and the interest and the energy to do that. That’s why he’s a good broadcaster.”

Paying it forward, McDonald shares his knowledge and experience with young Orioles starters Kevin Gausman and Dylan Bundy.

“When I see him here, I always make sure to talk to him,” said Gausman, who first met McDonald in 2011 when he was pitching for LSU and McDonald was the team’s television analyst. ” … I was lucky enough while I was in college, me and a couple of guys went [to McDonald’s house] for dinner one night. We came over and saw his Golden Spikes Award.

“That’s when I found out he played basketball at LSU, too. He had a basketball jersey, and I was like, ‘Whose jersey is that?’ He said, ‘It’s mine.’ OK, that’s cool.”

McDonald said he’s happy to talk shop with the young pitchers, but he makes it a point not to force his opinions on them.

“I don’t want to do that because I know how it was when I was a player and an ex-player would come around,” McDonald said. “But if they ever ask me a question about something, of course I’m always there.”

It’s that approachability and genuineness that has endeared McDonald to Orioles fans throughout the years. The feeling is mutual.

“I look forward every year to going back to Baltimore and mingling with the fans,” he said. “My favorite thing is getting a crab cake and a cold beer. I still bump into some of the same ushers in the ballpark that were there when I played, and we have some talks. … I just love Baltimore.”

Issue 244: May 2018